Sometimes, adding something to a codebase is routine. One that is so well-defined, that someone can point you to the exact files and lines in a codebase where changes are necessary.

Instead of telling people what to do where, at Dado, we wanted people to be able to discover and follow these steps autonomously.

Tracking lines of code externally

When I say documentation, a lot of people will think of tools like Confluence or Slab. Unfortunately, it’s incredibly hard to keep external references to a codebase synchronized, simply because code is so volatile. We may get away with documenting slow-moving aspects, like system design, architecture, principles, and patterns, but specific files and lines of code may change daily.

We’ve tried to use Bookmarks to mark points of interest. This extension lets you mark specific lines in files, tracks these as you make changes, and saves them in a file in your repository. This may work well on a project you’re working on alone, but less so in a team. Sadly, the file containing the bookmarks frequently had to be updated manually after a rebase or merge. After forgetting that a couple of times, the bookmarks no longer referred to the code we wanted to track.

We concluded that if we want to document these steps, we can’t do that externally — it has to be in the code. This way, the reference sticks to where it’s supposed to be unless deliberately moved.

Inline guides

Similar to how JSDoc annotates functions and whatnot, we came up with a comment format to annotate points of interest for certain tasks. It’s inline, right next to the relevant code.

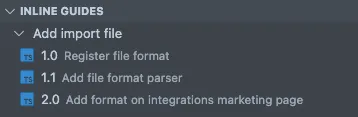

Let’s say we’re working on an app where users can supply information by uploading a file with tabular data (e.g. CSV, Excel, Apache Arrow, etc.), and we want to write a guide for adding a new file format, we could add these comments to make a multistep guide:

// @guide Add import file - 1.0 Register file format

// @guide Add import file - 1.1 Add file format parser

// @guide Add import file - 2.0 Add format on integrations marketing pageEach guide has a name which serves as a guide identifier. The step number is used for ordering. That might not be necessary as you’ll probably complete all steps before shipping, but can be useful to build a mental model. Lastly, there’s a step description to describe what action is required for this step.

Where to find them

It’s cool we have these guides, but we can’t expect users to scan all files in a codebase until they find them, can we? Initially, we started doing a full-text searches for @guide to find the guide we wanted to follow, and then searched for @guide [name] to find its steps. Sadly, the list of results is ungrouped and unsorted, so we set out to create a better list.

We first searched these with grep, a Unix command-line utility. The following command will scan for @guide recursively, starting from the current working directory:

grep "@guide" . --exclude-dir=node_modules --ignore-case --line-number --recursiveI expected it to be slow, but it’s surprisingly fast! Using the command above, a codebase of 500,000+ lines of code gets scanned in about half a second. You can then parse the output and sort the results.

Despite being surprisingly fast, a faster alternative is using ripgrep. Ripgrep is a command-line utility that’s similar to grep, except that it’s cross-platform and also takes your .gitignore into account, so it automatically skips over ignored files. The following command is pretty much equivalent to the grep command from before:

rg "@guide" . --ignore-case --hiddenWe realised we could list the guides with a Visual Studio Code extension, and built the Inline guides extension. Instead of fiddling in the console, it adds a pane listing all guides and lets you navigate to these lines with a single click. Note that the plugin isn’t polished — we built it to make it work for us.

How is it?

Inline guides have proved to be a great tool to make sure we don’t miss a step, even when we find ourselves in unfamiliar places. It lets the team members dive into deep waters littered with floaties for them to latch on to. It also served as a checklist for developers who know exactly where they need to be, making it was useful for the entire team, regardless of their level or familiarity with the codebase.

Limitations

Some files that could have a guide in them, might also be included in the .gitignore file, like configuration files that contain secrets. Our use of ripgrep means @guides in these files aren’t included in the list. That can be a bit of a bummer, though ripgrep can be modified to use a custom ignore list, instead.

Another thing is that you can’t add @guide comments to files that don’t exist. If a step requires adding a new file, we can add a guide to potentially relevant import statements, which don’t exist if the file is loaded dynamically.

Closing thoughts

This approach of directing people through a codebase works amazingly well, especially when autonomy is valued. The applications are limited, though. There’s little use of describing guides for tasks that aren’t repeated. At best, one could use them to create some sort of onboarding tour.

If you do have a codebase where a part of it is extensible, and you’re levering that extensibility frequently to add in new features, inline guides are amazing.